A Case of Postdiluvian Tristesse: The Encounters in Sam Branton’s Deluge

‘Neither culture nor its destruction is erotic; it is the seam between them’

There is a strange poem by Andrew Marvell about a nymph and her pet fawn. Written in the mid seventeenth century, ‘A Nymph Complaining to Her Fawn’ is a poem of three parts, revolving around a central act that recounts the intimacies of their relationship. This intimacy is physical in that it is rooted in the senses – glimpsed at through heady descriptions of the nymph suckling the fawn with milk-dipped fingers, and the fawn feeding on roses ‘until its lips e’en seem to bleed’, pressing the bloody pulp onto the nymph’s lips in a bright red kiss. This is the story of an inter-species relationship that is tender and erotic and odd without being straightforwardly sexual or pornographic, suffused with a libido that Matthew Augustine has described as ‘tactile…rather than genital’. In other words, arousal is a creature of many eyes and ears and fingers and holes, and a discussion of the erotic should not be limited to genitalia.

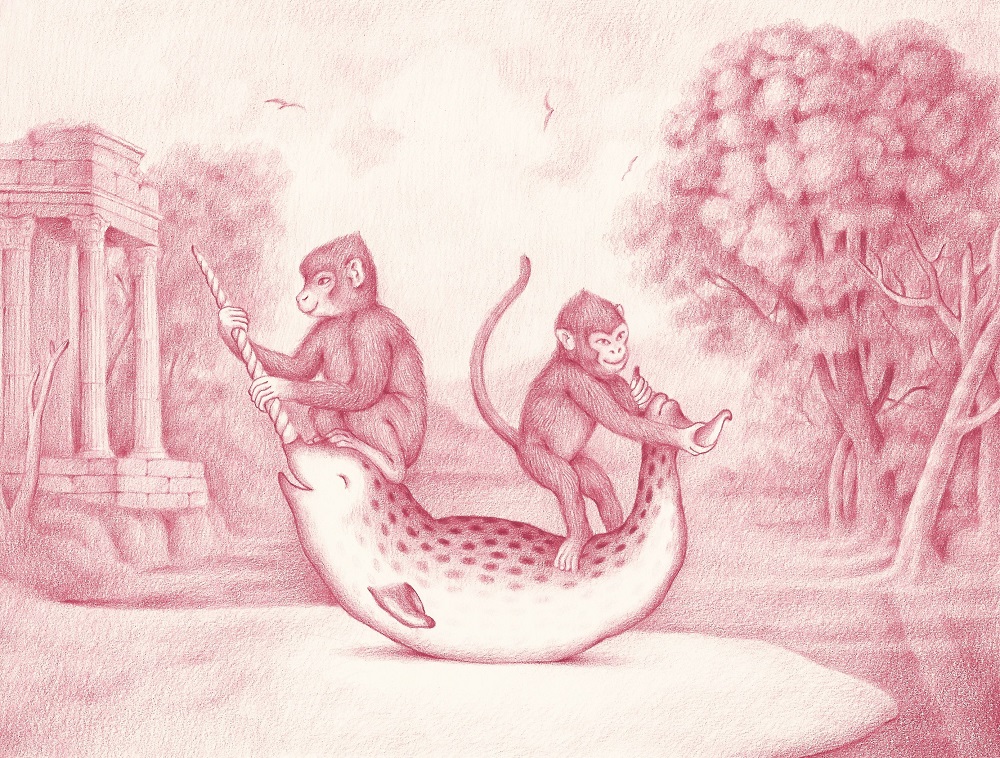

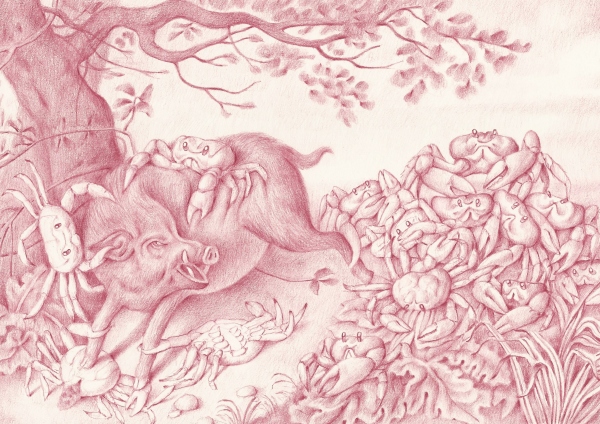

Marvell’s poem can be read as an exploration of the possible acts and resulting sensations that make up the texture of an erotic encounter. Small in-between acts such as licking, biting, sucking and squeezing are not necessarily pornographic; they oscillate between sexual and non-sexual contexts with ease. In more general terms these are acts through which one thing experiences the physical particularities of another, with all the surprise, pleasure and/or confusion this might entail. The thrill is in the contrast; in the incredibly soft, and secretly wet. An inside that is seductively different to its outside; a silk-lined coat, baked Alaska, battered fish, a humid bar beneath a cold street at night. It is at this juncture that the animal worlds of Andrew Marvell and Sam Branton might be said to converge: in moments where pincers press on soft round flesh and furry fingers on rubber skin, in a new series of bestial encounters.

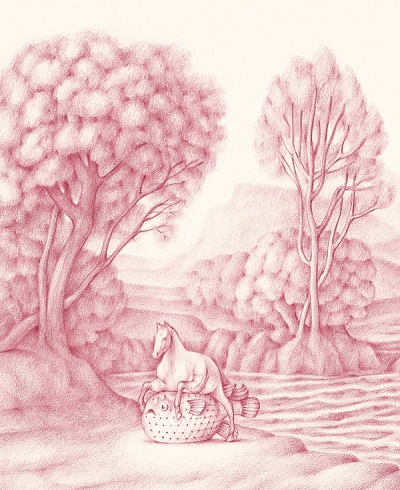

Deluge, Branton’s 2015 collection of drawings, is set in the aftermath of a great flood, and its resident creatures populate their newly unfamiliar surroundings in confused and unexpected couplings. The landscape itself is eerily unscathed, possessing a miraculous elastic quality whereby woods retain their clearings, trees retain their branches, and streams and pools hover calmly in the background as if willing you to believe that water was ever disruptive. Not a drip or a rip to be seen. The sole indication that a natural disaster has recently taken place is in the creatures themselves, and even then it is not the creatures who have been altered but their contexts and the company they keep. In this way, the tension within Deluge’s scenes is not found in the place or its destruction, but, to use Barthes’ terms, in the resulting seam –where things meet across the divide. This sense of stepping over boundaries, paired with the eeriness of an immaculate landscape, lend the drawings a powerful dreamlike quality.

Branton’s pastoral landscapes are directly drawn from those of Poussin and Lorrain, reconfigured in blushing pink pencil. As those two artists knew well, secluded woodland spots are perfect for illicit encounters – whether it’s Diana spied bathing in a secret pool, the quietly charged gatherings of young men and women in Watteau’s woodlands, or simply centuries of everyday banging al fresco. Clearings are nature’s keyholes; private openings bounded by thickets and curving branches that dim the evening light. Eroticism loves to be framed; the more voyeuristically and intimately the better. Marvell achieves this in structural terms: nestling the interactions between nymph and fawn in the central passage of the poem, framing it between its narrative-led outer parts. Within the world of the poem, the fawn itself is kept in the nymph’s enclosed garden, its lithe body hidden from sight by overgrown lilies and roses – like a painted miniature kept in a rich thrill-seeker’s pocket.

Branton likewise utilises the erotic voyeurism of framing in the structure of his work – the scenes in Deluge are almost always captured in clearings, which act as a frame within the physical frame of the piece – taking a central position in the composition and viewed squarely from eye-level perspective – his animal subjects taking a reluctant centre stage.

The combination of the unreal immaculacy of the settings with the occasional stone plinth and ruined temple that are scattered like props, imbue Branton’s scenes with a sense of the theatrical. Add a hint of voyeurism and an undertone of cruelness might appear – natural traps set to capture scenes of struggle and confusion. Branton has noted the influence of film on his work and this might account for this sense of scenic theatricality. Each drawing is hyper composed with a camera-like quality that is precise and coolly detached from the plight of its living subjects, and lit with the exactness of film set. Branton shines an invisible spotlight directly at his victims, casting low shadows and highlighting the gleam of their exposed bellies.

Text by Miranda Stuart