Alice began her career as a copywriter and graphic designer, eventually responsible for positioning global brands, and developing and executing their marketing and communication strategies.

Returning to her creative roots several years ago as an artist/photographer, Alice has produced five exhibitions, including The Iceland Trilogy, held at the Embassy of Iceland in London, and Black, White and Red held in Nice, France.

In what way has your previous career influenced your work?

Two ways. First of all, I know that communication that appeals to the head and the heart will be more effective. What do I mean by effective? Engage; get attention; pursuade; shift attitudes; make an impression; be remembered.

A message that resonates on both levels will usually have a deeper effect.

Secondly, I learned to never make assumptions about how people will respond to a message or a creative work. Every response is valid, and second guessing is not wise.

For both these reasons it’s vital for me to listen to viewers and understand how they feel about a work; what they think about a work; what they like and don’t like; which is just as important. Asking 2, 20 or 200 people could result in 2, 20 or 200 different responses. And there is no right or wrong, there’s only how that individual responds. So very simply, I try to create work that engages on both levels.

Who or what is your greatest influence in your life and art?

The answer to this is not singular. To some great extent, I have to credit my parents with nurturing the seeds of those characteristics that make me Me. My mother instilled in me a romantic’s desire for adventure, and my father – who, in a different time and place could have been a successful pen and ink illustrator – fostered in me a sense of curiosity about the world; applauded the virtues of attention to detail; and as a young girl, introduced me to art. Both of them encouraged my talents (I am also a writer, and began life as a classical pianist), and taught me the fundamental importance of believing in, relying upon and trusting myself. The second significant influence on my life was the time I spent in Israel as a teenager, where I completed high school, and lived through a war. Aside from stimulating a lifelong appetite for travel, the years I spent there taught me not merely to tolerate, but to seek out and applaud “difference”; tutored me in resilience; and gave me the courage and confidence to choose the more difficult road if it offered what I wanted.

The third influence is my education, where I gained a deep understanding that people are driven by a complex mix of rational as well as emotional factors. I try to apply this insight to my art, creating images that I hope appeal to both a viewer’s head and heart.

All this underpins my life and my work, and helps explain how and why I do what I do.

Where do you call home and where did you study?

I travel extensively and I’ve lived in France for the last year or so but London is my permanent home. I completed high school in Tel Aviv, and have three degrees from York University, in Toronto, Canada.

Do you have a favourite piece of your own work?

It could be that an image evokes the memory of a certain place or experience, or I am delighted with the texture of air that I have been able to achieve. Certainly, as time goes by and my style and technique evolve, my thoughts and feelings about earlier work change.

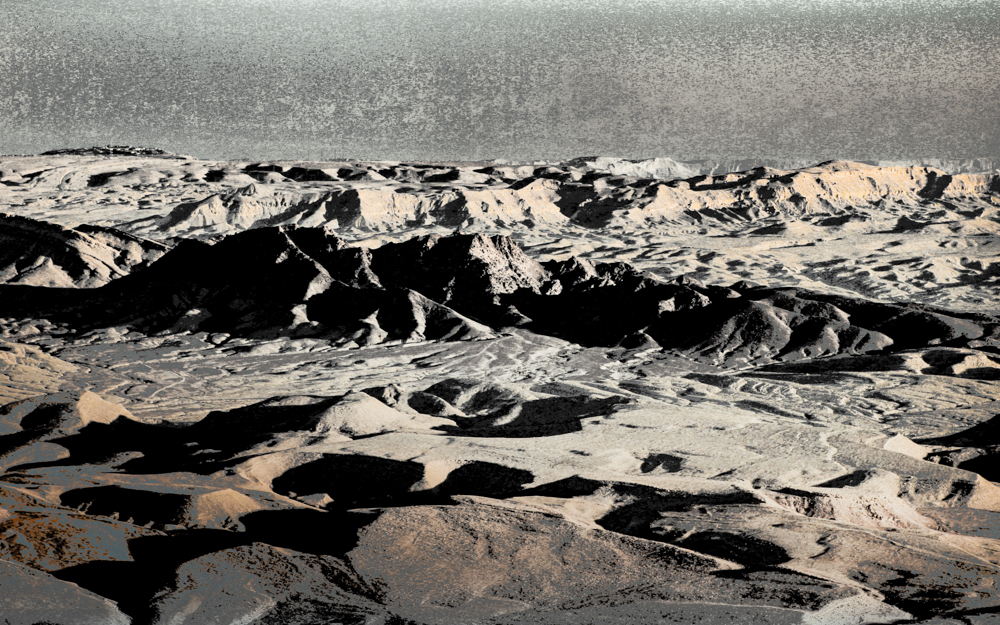

It also is difficult because my work covers a range of themes. I am probably best known for landscapes and seascapes, but I also have exhibited wildlife (Merlin’s Forest), produced series of abstract art based on surfaces (Walls), and have a number of aerial series (LA Nights, Nevada

Desert, Over North). And of course, I also do “straight” street photography, always adding to my In Public Places collection. So there are many images that move me for different reasons, but there is not one piece that I favour over everything else.

Texture seems to be a re-occurring ‘motif’ as it were in your work – why is this?

Texture evokes a sensory response, and whether it is felt with the eyes or the skin or finger tips it’s one of the ways we engage with and understand the world. To me it’s as natural to explore texture as it is to explore colour or shape. It’s also a way to move beyond the flat surface of a photograph.

I have an image from Iceland called Mountain, which has received a lot of attention (including being auctioned at Christie’s and making the CultureLabel Top Ten Artworks List). It has quite remarkable depth. So much so that I have seen more than once, in exhibitions, people actually looking behind it, to where it is hanging, to see how it’s projected! That’s what I want to achieve with texture….people literally reaching out to touch the image.

Your work is heavily influenced by your travels. Do you travel specifically to photograph certain sites, or is this a happy by-product?

Travel is my work, and travel plans are about obtaining new source material for artwork. I never travel to a country to see one thing; rather, I let the country set the context, and then within that framework I explore as much as I can.

Sometimes a specific destination is chosen, such as Iceland, or Jordan, or sometimes the means of travel provides the context for the photography – the Wake series, for example, was shot from a boat as I travelled from London to Marseilles through the locks and canals of France. I also have lived in many different countries – India, Turkey, Israel… And of course, these have provided extraordinary material from which I have drawn.

Your work is an interesting mix of digitally-altered photography with multiple layers of edits. Is your process of alteration systematic or more organic?

People frequently ask me what software I use, but my work is not about software or digital technology. That’s why I have a problem with the term “digitally manipulated work” as a descriptor. In terms of how I think of my work, it puts the emphasis on the wrong thing. My work is first about the image, without which there is no art, and then it’s about having a vision for interpreting it.

At the end of a shooting day I look at the photographs I have taken and start to think about what I want to do with them. I have a good sense as to the extent I want to push the envelope and try something new, and of course this excitement drives my enthusiasm to take the images to the next stage of development.

I start with the same workflow approach, but I always allow myself to be steered by what I see happening as I work on an image. I do not believe in process for the sake of process. If something unusual or unanticipated starts to become evident, I go with it. The fascinating thing is that the end result may be nothing like the image I thought I would create. When I speak in terms of “the picture telling the story”, this is what I mean.

In some cases an image can be completed in different ways, each equally intriguing and strong, but even a subtle change can result in conveying very different feelings or moods. If there are enough images, I may create smaller series within the collection, in several styles. If it is a single image, I ask myself: what is it I am trying to communicate, and what response do I want to evoke?

What has been your most exciting commission to date?

Certainly the Year of the Horse commission was a great challenge, but also hugely satisfying. My client (5500 km away) did not provide a formal brief, so I had complete freedom in terms of creative approach. I produced a number of alternatives, each unique in style, and I was very pleased with all of them. So we each selected our first choice, and were delighted that independently, we came to the same conclusion. He had a fantastic response to the image when it was published, but what really pleased me was that this was his first commission, and he said he found the experience very enjoyable.

How do you find working to commission? Do you find it pushes your work in new directions?

There are few things as exciting as a new commission!

“New directions” can mean many things: new subject matter, new creative approaches, new technique, new ways of thinking, new end user…The push into a new direction certainly can come from a client, and it is always wonderful and welcome when it happens. Having said that, I also believe that the drive must come from within. No one pushes me more to be innovative than I push myself.

For many years I was the one commissioning artwork, so I have a good understanding that effective communication between artist and client is critically important. I am equally comfortable tackling a tight and specific brief, or starting with a blank page. Both have their challenges and rewards. The real trick is to achieve a clear understanding of what is desired before the project begins; most clients know what they like when they see it, but many find it difficult to describe up front what they want. I believe it’s the artist’s responsibility to help the client articulate what they are looking for; without this effort at the start, the process is bound to be lengthy, and fraught with frustration (by both parties) and wrong turns.

Which 5 pieces of artwork would you choose to have with you on a desert island?

Only five? What a challenge!

– Any one of Egon Schiele’s trees or landscapes. He was as much a master at filling the canvas with sparsity as he was working up the most specific details; of coercing awkward straight lines as lovingly shaping bended ones, of composition and shadows and layering…

– A Frederick Remington bronze sculpture, because his ability to achieve balance was as magical as his ability to evoke the gigantic, raw feelings associated with America’s “Great West” at the turn of the century.

– Cindy Sherman, for her brilliant, unrelenting exploration of self-reinvention. Each picture is brilliant but the impact when seen/understood as a body of work is unforgettable.

– Chagall’s bride and groom flying to the heavens on a horse, from Song of Songs lV, for the passion of his reds, his incomparably imaginative interpretation of the Biblical text, and the image’s ability to make my heart absolutely pound with joy and love.

– Victory at Samothrace (aka Nike at Samothrace), because it simply defies gravity, forces me to imagine what isn’t there, and makes me believe the unbelievable: I can feel the wind on my cheek as she descends.

Who is your favourite artist at the moment?

I recently visited Bilbao for the first time, and spent an enthralling morning at the Guggenheim. The spectacular Richard Serra installation entitled “A Matter of Time”, comprising eight enormous sculptures of weathered steel that you walk through, is like nothing I have ever experienced before.

Sam Taylor-Johnson’s “Sigh” – a multi-screen video of an orchestra playing instruments without the instruments – is also a brilliant work on exhibit.

Spontaneity or planning?

Both: for some things you need to be prepared, but you always need to be able to seize the moment/opportunity.

What is the most challenging aspect of your work?

Without a doubt, trying to keep the work fresh and individual, with each image and series, and pushing myself into uncharted waters. I consciously try to avoid falling into a pattern of what’s easy or familiar, which means both finding/deciding new and interesting subject matter, as well as trying different and often difficult techniques in the work flow process.

A lot of your work uses a range of muted colour tones such as brown, black, grey and white – why is this?

It is true that a lot of my work currently on my website is monochromatic or uses muted tones. I take this approach for two reasons. The first is that it helps create the atmosphere I want to project.

The second reason is because colour can be a distraction. Think of what I would call a “beauty shot” of a castle on a hilltop, the type of picture you would see in a travel magazine. It would not be unusual for that kind of picture to evoke a “wow” response. But if you take that image and replace colour with muted tones, you might find yourself looking into shadows and lines which is a very different experience of the image. In the first instance you tend to still be an objective observer; the second circumstance has a greater chance of drawing you closer.

But I need to correct the idea that I only work in muted colours. I have produced a number of series where colour is fundamental to the success of the image. The Stream in Glun images in my ArtCircus portfolio certainly feature colour. My abstract series Walls are about colour, as well as texture.

And I just finished a series called Becoming Harlequin where in 5 images I take the face from a b/w charcoal sketch through a highly saturated painterly face to a smooth almost airbrushed face where the viewer struggles to determine not only whether the face is male or female, but whether it is human or a mask.

Lastly, I should also say that my work for Bridgeman Images is, as a portfolio, pretty colourful. That’s because licensing work is created for a commercial market, and those images work differently: they need to immediately capture the attention of the viewer, and instantly communicate a sponsored message. Colour helps achieve those objectives; the viewer is not being asked to consider the images as gallery art, per se.

What do you consider before taking a photograph? Do you actively think about compositions and lighting or is it more spontaneous?

I always think about composition. Always, always, always. But I take pictures spontaneously. I do not plan shoots, or set up or stage scenes, or even use lighting attachments. My photographs are immediate. That doesn’t mean I don’t know what I want to shoot, or what I want to walk away with, it just means I need to be thinking about a lot of things simultaneously, and I need to “think on my feet”.

I do think about lighting, but it’s not as critical as composition, because I can adjust light in the work flow process. Sometimes I alter it completely. But a poorly composed image is a poorly composed image. A few weeks ago I went to Venice for three days just to take photographs. I knew I wanted images that would allow me to interpret the Venice that most people think of. But I did not plan what I wanted to shoot. The opposite. I planned on getting lost and seeing where that led me. So of course, I had to deal with whatever the situation was when I got to a place I watched to shoot – on the spot!

You are a writer as well as a visual artist. Does your writing influence your photography or vice versa?

Interesting question. I am more than half way through a book of 12 thematically related short stories which will be accompanied by 80 of my images. I started life as a writer and pianist, but this book started as an art book. How it evolved is a lovely tale, but it was a spontaneous response to an off the cuff comment made by a friend that prompted me to write the first story. Once I had written the first story, I knew I wanted to write the other 11.

So in that way the images were a catalyst for the creation of the stories, but in terms of creative approach they developed independently. What I would say is that just as I constantly push for new approaches to originality in my images, I set myself the objective of making each of the stories unique in terms of narrative voice, characterisation, setting, time-frame etc. So they share the same artistic goals, but that’s all.