Do you come from a creative family?

Yes. My mother used to be a skilled calligrapher, and my father is a dab hand at painting. Most of my relatives are fairly artistic, one notable being John Hamilton Mortimer, a neoclassical painter who went completely mad and died young. I’ve inherited a drawing of his of King Lear, in which the maniacal Lear is depicted with his enormous windswept beard and huge glaring eyes. I remember being horrified of this drawing when I was a child, and of later loving it. I’m guessing that a love of art is in my blood, though I’ll forgo the madness.

You said you began studying the History of Art at the age of sixteen. The influences are clearly evident in your paintings. Do you feel studying the Art History is an important process for an artist to go through? How do you think it helps with an artist’s practice?

Well, the most important thing is simply to express yourself. But if art is your oxygen, then there’s nothing more interesting than to study the great artists in depth. It’s helpful in that you can examine just how and why mankind has expressed itself over time, and just what dizzying pinnacles of creativity we’re capable of. We can then strive to build on that, and to eventually create even greater works of art.

You also mention travelling, could you talk a bit about how this affected your practice?

I love adventure and I’m very stoic, so the more gruelling the travelling is the better. Novel experience and suffering build character and feed the soul, giving as much fuel for art as for good anecdotes, which are much the same thing;

One trip which comes to mind was to the Gobi desert in the winter. I was staying with a family of Mongolians who clearly disliked me, and I came down with violent food poisoning after eating the offal of a goat they slaughtered inside the yurt before my very eyes. Later on, as I crawled out into the freezing tundra in my long-johns to go throw up, some stray dogs emerged from the blackness and approached my retching form. I thought they were going to attack me, but instead they began eating my vomit as I produced it, which was somehow much worse, lapping at the ground and licking my face until I finished.

Though that does admittedly sound horrible, I have a keen sense of the humour and the beauty in things which otherwise seem only awful and grotesque, and I think this outlook can be seen in my pictures.

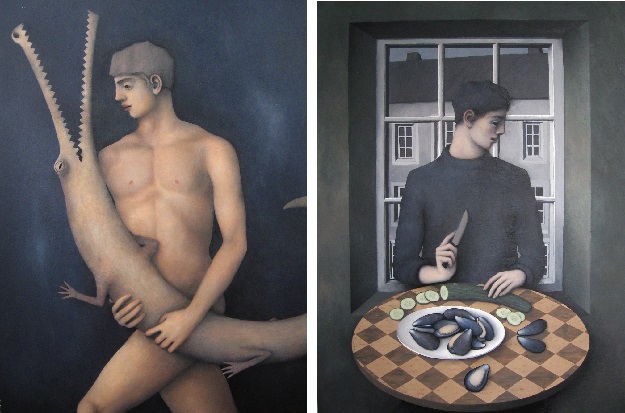

Do your subjects inhabit our world or a slightly different world?

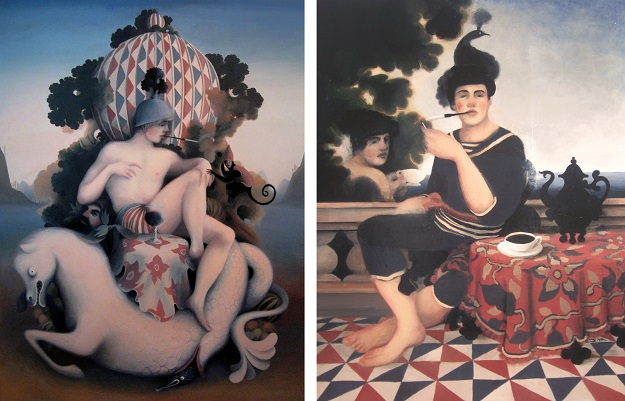

A bit of both, but the work is all rooted in the real world. I’m certainly not trying to set anything in some kind of magical fairyland. However, it would be tedious to just paint what’s in front of me, as art is about expressing oneself and giving substance to the soul, and quite frankly real life, as it is, is so boring. When I was younger I drew a picture of a boy riding on a giraffe (the chair lashed to the nodules on the giraffe’s head). This was just after I had been riding on an elephant, and thinking to myself all the while “This is all very good, but riding a giraffe would be even better.”

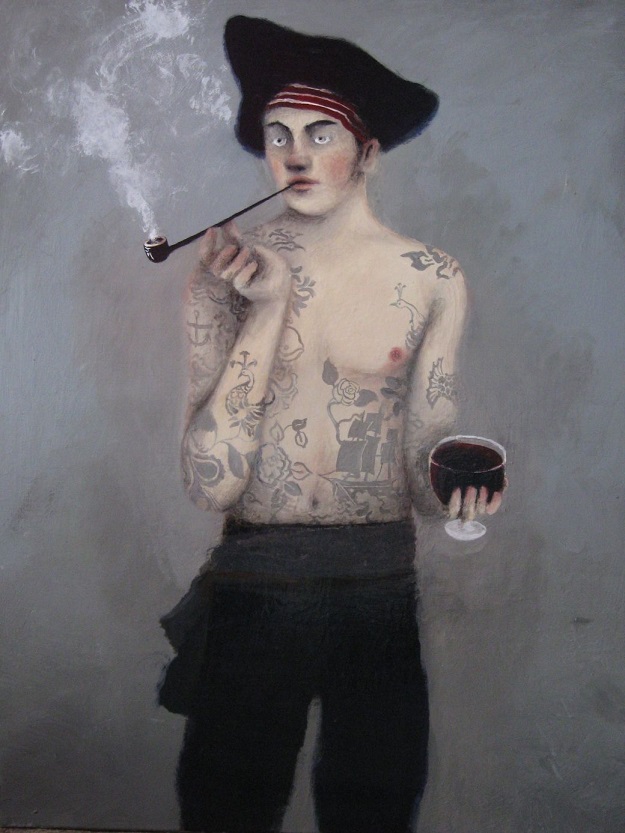

So it’s my own skewed version of things that I put in the pictures, of how I would fancy the world to be. Obviously the creative process is usually a touch more subconsciously driven than this, but I think that making images along these lines results in art which is at least passionate and wholly individual, and at most which serve as metaphors for the human condition, such as it is. That is my aim.

You mention an interest in immoral fin de siècle literature. Can you talk about some the influences on your work?

That sounds incredibly pompous, but yes I think the artistic and literary output of that era is most interesting. There’s too much to go into, but just to pick the big daddy of degenerate literature, I’ll mention Against Nature, by Huysmans, which has inspired me no end. It is a novel without a plot, and essentially the guide book to decadence, notable for being identified as the poisonous French novel which goes on to corrupt Dorian Gray. It explores the artistic and spiritual tastes of a reclusive French aesthete, who during one chapter has a live tortoise gilded in gold and encrusted with semi-precious stones. The tortoise dies. It is a really great book.

Interesting fact: Apparently, if you have read Against Nature, and ask someone at a party if they also have, and they say yes, then they have to go to bed with you.

What is the main distraction from your studio?

I’m a great outdoors man at heart, so would always rather be outside. That and the pub of course.

Have you ever changed parts or kept things out of a painting that you think might be too weird/offensive/shocking etc. Or because it might affect the sale of a piece?

Ah, then you’ve obviously not seen my epic panel, The Last Days of Sodom and Gomorrah!

Just kidding. But no, I haven’t, and though really I’ve never made anything especially risqué, I think you can get away with a lot provided you do it with subtlety and panache. Whatever little abominations I have slipped in I’ve only done so within the context of a piece, so far without scandal. It’s vital to be challenging, and to express yourself, but so long as you’re not being crass and blatant. As the bloke said, ‘There’s no such thing as moral or immoral art. Art is either well made, or badly made, that is all.’

If time and money was not an issue, what sort of project would you like to work on?

I’m starting to warm to the idea of an epic panel depicting The Last Days of Sodom and Gomorrah. But no, I thought about this one, and I don’t think time and money are particular obstacles to painting and drawing, as it would be to sculpture. As long as you’re patient and have a single minded resolve you can usually make whatever you want, however ridiculous and whatever the scale. If I were suddenly given a lot of money (which for wealthy people reading, I wouldn’t mind) then I’d make exactly what I’m making now, only I would now have a pet lion.

How do you feel your work has developed since you last exhibited?

I like to let things come naturally and to go with the flow, and for each piece to be a standalone work. But saying that, after the last show I had my usual little break, and went on camping trips to the moors and the coast, and as an experiment made life sketches of my chums, myself, and of what we were doing and seeing.

They are the most boring things I have ever drawn. However, it was a useful exercise, and along with some other experiments I made, I’ve used various elements of these sketches in the designs for the new paintings – a tor from this landscape, a table from that pub – which I think has brought a certain new emotion to the atmosphere of the works. I’m most pleased with how they’re shaping up, and am very excited to see them all finished and on display.

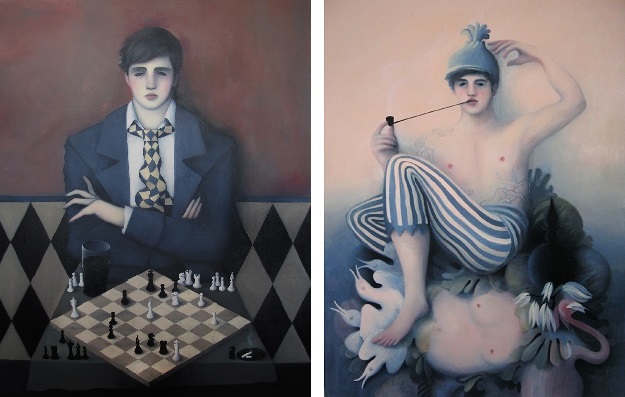

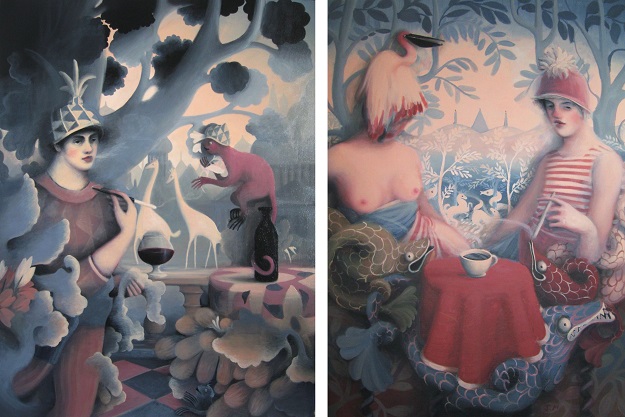

James Mortimer’s new paintings will be on show in ‘Pipe Dreams’, alongside ceramic artist Claire Partington at the James Freeman Gallery from the 22nd of November to the 21st December 2013.